- Opera

Invoking the Gods

by Tobias Staab, Mon, Sep 1, 2025

What is real? Or, to ask a slightly smaller question: How can we recognize what is real? Since its beginnings, Western philosophy has been skeptical of the phenomena presented to our senses. Not only Plato, Kant, and Schopenhauer distrust the sensory excess that floods our perception and leaves us alone in a fragile coordinate system between the self, the world, and God. In Indian philosophy, particularly the Vedanta school of Hinduism, the illusory nature of the visible, material world is also asserted. Here, the veil of Māyā (Sanskrit for ‘illusion, magic’) covers the true, absolute reality (Brahman), which always bears a mystical and transcendent dimension. Today, we know for a fact – since at least the visual turn of AI technologies – that the images that flicker across our digital devices every day cannot be trusted. But how can we discern the true reality we suspect lies behind the mirages, simulations, and deepfakes? What secret awaits us if we climb out of the cave and take a look at the back of the matrix? And what physical or spiritual practices would be able to give us access to this reality?

How can we discern the true reality we suspect lies behind the mirages, simulations, and deepfakes? What secret awaits us if we climb out of the cave and take a look at the back of the matrix?

Perception put to the test

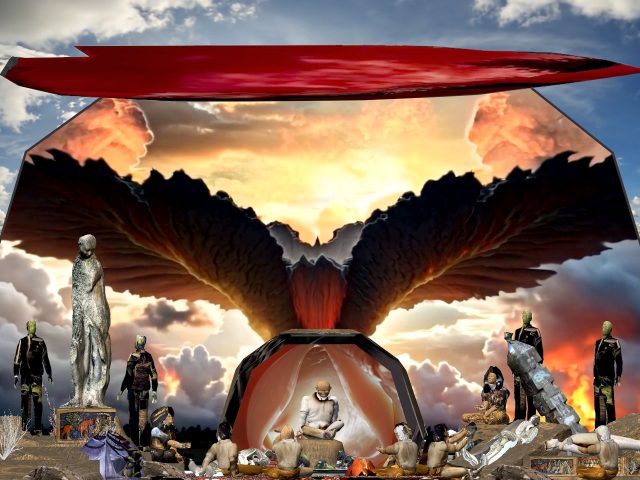

The artist couple Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg creates spaces in which one can lose oneself. Their artificial worlds exist somewhere between theatrical performance, collective ritual, and video installation, and in them, perception is constantly put to the test. This starts with the stage architecture, which is completely covered with projections, making it impossible to know for sure whether the spaces that open up are real or virtual. It extends to the performers, who seem strangely detached and almost uncanny, moved by forces that don’t come from within themselves. At first glance, this thoroughly artificial world presents itself as a future vision of a multi-sensory overkill, where the real disappears and only another phantasm hides behind every illusion.

Susanne Kennedy once described her aesthetic as an attempt at a total theater. By referring to Erwin Piscator’s famous term, she not only alludes to the theater as a place where different art forms and media come together – body and space, light and video, music, speech, and song, stage machinery and the auditorium. Kennedy also describes an approach that is meant to have a total effect: a theater that bundles all expressive means to achieve an immediate and overwhelming impact. A theater that connects with the bodies of the audience, absorbs them, and takes them along.

The aesthetic of Kennedy & Selg’s work places their theater in a post-digital present where the lines between virtual and analog reality have become blurred. Even more so, it's a present that has given up on distinguishing between simulation and reality. The resulting aesthetic, in which multiple levels of reality always exist simultaneously, which overwhelms and irritates, and which connects so astonishingly effortlessly with our current lived reality, has had a lasting influence on European theater in recent years and inspired an entire generation of young theater makers.

It was only a matter of time before Kennedy & Selg would venture into the opera. They made their debut in 2022 with Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach, an opera installation where visitors could choose whether to watch the events from the audience or to venture directly onto the stage to experience the opera among the singers and performers. A ritual-like movement vocabulary combined with Glass’s repetitively pulsating composition created an immersive pull that produced an almost psychedelic effect.

Archetypal images

With Parsifal, the artist duo now takes on their second opera project, Richard Wagner’s final composition, which he appropriately labeled a ‘Bühnenweihfestspiel’. This term is more than just a genre designation. It's an artistic and spiritual program that leaves traditional opera dramaturgy behind and elevates the stage event to the status of a sacred act. The combination of ‘stage’, ‘consecration’, and ‘festival play’ points to a holy, celebratory act that takes place within a specific framework and is intended to bring about an inner transformation in everyone present.

Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg take this framing very seriously. The medieval verse novels by Chrétien de Troyes and, above all, Wolfram von Eschenbach, which lay out the Parsifal myth as an adventurous hero’s journey, are already distilled to their essence by Richard Wagner. In the opera they become an inner journey for Parsifal. The stations and encounters manifest themselves in archetypal images that anticipate concepts of the unconscious as later described by Carl Gustav Jung, in particular. They appear more as stages in a hero’s spiritual maturation process, who, over a lifetime, must forge a relationship with the world, with God, and not least, with himself.

Spiritual insight

In doing so, Wagner underscores his universal claim by presenting a remix of different religious and philosophical approaches. In Parsifal’s world, the cycle of Samsara – the Hindu concept of death and rebirth – and the Christian promise of salvation seem to coexist effortlessly. Parsifal’s character seems to be shaped equally by elements of both Jesus and Buddha. Wagner drew inspiration from the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, one of the first Western thinkers to engage with Eastern philosophies. Schopenhauer connects the ‘veil of Maya’ described at the beginning with the ‘principium individuationis’, which makes the world appear to us as separate individuals and objects in space and time, and in it, he identifies the primal cause of suffering. However, while Schopenhauer derives his notorious pessimism from this, Wagner, at the end of his life, searches for a perspective that affirms life and shows a way out of the existential dilemma. His Parsifal, by ‘knowing through compassion’, finds a way to overcome the fragmentation of being. World, God, and the self fall into one and become a divine unity. Instead of a moral catharsis, Richard Wagner introduces a spiritual insight.

Wagners Parsifal, by ‘knowing through compassion’, finds a way to overcome the fragmentation of being. World, God, and the self fall into one and become a divine unity. Instead of a moral catharsis, Richard Wagner introduces a spiritual insight

‘The first theater was the temple’, Wagner states in his text Kunst und Religion, and it is this realization that connects with a search movement that has defined the core of Kennedy and Selg’s work for several years. It is a search for the origins of theater, for rituals that connect with the religious roots of the art form, and for practices that are capable of creating community. They find inspiration in religious liturgies, tribal initiation rituals, and also in the pre-Christian mystery plays of Greek and Egyptian antiquity, in which cultic and theatrical elements interpenetrate with each other.

‘To start from religion is to start from a social cultural system in which there is communication with the gods’, writes Jean-Luc Nancy in an essay on the event of theater. ‘As soon as this connection dissolves, all that remains is drama, which means “action”. Action is precisely what happens far from the cult. (…) The cultic gestures bring about effects from which one desires salvation.’

Kennedy and Selg’s work is a search for the origins of theater, for rituals that connect with the religious roots of the art form, and for practices that are capable of creating community

In Parsifal, too, the ‘salvation’, which aims at the spiritual perfection of humanity, cannot be achieved through the renewal of external circumstances in the world. It occurs through a change in an inner disposition that affects not only the character but includes everyone present. The total theater of Susanne Kennedy and Markus Selg is much closer to such a direct invocation of the gods than to the idea of a psychological theater that is committed to representation, and thus, to action. Their Parsifal is a search for the archaic and spiritual ground on which the myth could thrive. In their theater, the audience becomes part of a collective that embarks together on a ritual path. And when, at the end of the opera, Wagner's music leaves behind everything that words could express – when the Grail motif rises through virtual veils and past AI-generated illusions into a vertical stream that resonates in the bodies of everyone present – it becomes clear that the true powers of theater are hidden there, in its religious roots.

Antwerp | Gent

Parsifal

Richard Wagner